The Art of Joel Silverstein

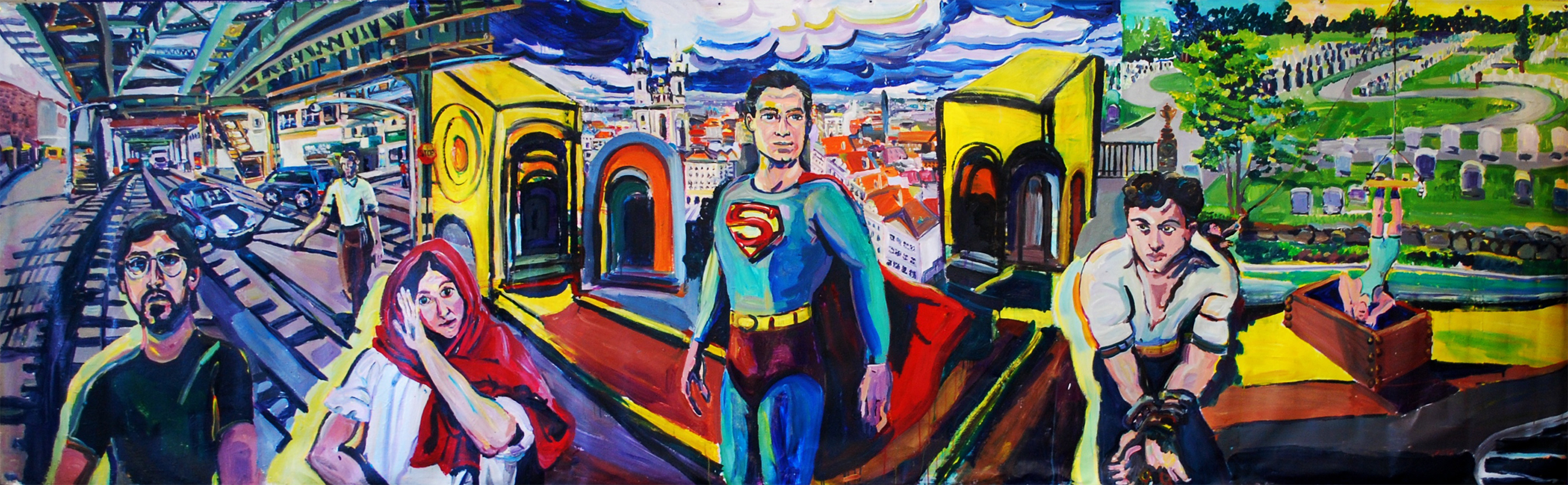

Joel Silverstein’s work represents a contemporary look at the visual tradition of history painting, the epic, and a modern evocation of the metaphysical through narrative painting. The artist, his family, friends, and other autobiographical material are the inspiration for a complex Magic realism. This creates a sense of myth derived from such diverse sources as dreams, cinema, Old Master painting, photography, comic books and collage. Western figurative painting, especially twentieth century expressionism are the initial models, using postmodern storytelling techniques. This clash creates waves of hot and cool contrast: description denoting observation paired with patent exaggeration, ironic takes on classic iconography, overt brushwork, visual anomaly evoking collage, commercial art, and alterior states of mind.

Silverstein was born in Brooklyn New York, near Coney Island. The strange environment of Brighton Beach with its ruined amusement rides and multitudes of people presented an early primer on multiculturalism, history, and religious experience. His own metaphysical and aesthetic conversion began with viewing a theatrical revival of Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments, 1956 at the age of six. Couple this with personal experiences of local Holocaust survivors, many living in Brighton during the 1970s and you have the makings of a heady, but nascent mysticism. Brighton Beach became the place of the Exodus and the Revelation; a zone where the secular and sacred, old and new, Id and Superego, collide to make aesthetic worlds. In the intervening years, the artist married, taught, moved to the New Jersey suburbs, and raised a son. All these experiences added to his understanding of painting, mythmaking, and personal expression.

In addition to ideas about experience and nature, the artist is a classic movie and comic book fan, often falling back on Golden Age and Silver Age tropes from both mediums. These may be experienced in a direct and straightforward manner, or ironically. It gives the artist a chance to comment on the nature of narrative, while evoking metaphysical states of mind without illustrating them. Often his paintings depict personifications of the individual split into different personae, such as heroes and monsters, which may be read in various ways. Personally, he favors an idea about myth like that of Joseph Campbell in the books, The Hero’s Journey, or The Hero with 1000 Faces, a reading of mythic stories seen through the lens of a map depicting the crises in a person’s life or a psychological lesson on a symbolic level. The artist holds an M.F.A. in Fine Art from Brooklyn College, 1992 but also an M.P.S in Art Therapy from Pratt Institute, 1982, Board Certified, ATR-BC. This orientation adds psychological depth to his use of iconography as well as narrative.

While myth may be global, the specifics of identity has preoccupied the artist for many years. The Anglo/American artist R.B. Kitaj, called for a Jewish Art in his essay, The Second Diasporist Manifesto, 1986. The question of “Jewish Art” is one which has preoccupied Mr. Silverstein since the essay’s publication. Like Kitaj, Silverstein feels that if there is authentic Jewish content, it is dependent upon how Judaism has responded both to Western Civilization and the visual arts. Mr. Silverstein is a Founding Member and Director of Exhibitions for the Jewish Art Salon, a New York based organization of over 500 professionals including: artists, curators, art historians and critics. It is the largest such organization in the world.

The following are descriptions of two works:

Ten Commandments and a Question, 2016 Acrylic on canvas, 60” x 96”.

This panoramic work was created especially for the Jerusalem Biennial, 2017. In it, characters from history, myth and pop culture freely mingle. The composition is derived from the Dura Europos synagogue mural cycle of 245 CE, Moses, and Aaron leading Israel Out of Egypt, 230 AD. Dura may represent the purest form of an indigenous ancient Jewish pictorial tradition. New York City flanks the left, while Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock is on the right side. On the far left is a figure derived from the German expressionist painter, Otto Dix, a doctor/drug addict representing avaricious or degraded behavior. Several characters are derived from Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. Anne Baxter as Nefertiri is superimposed in the sky as a symbol of hope, or of archaic memory. Moses is present, as portrayed by Charlton Heston twice, once at the center of the painting with his brother Aaron as played by John Carradine. Right, Moses is also rendered as an older, more conventionally “Biblical” patriarch, complete with whitened spiritualized locks, next to Yul Brynner as the Pharoah Ramses. The center of the painting is dominated by a figure cringing in terror before the oncoming Red Sea, cribbed from a Depression era The Shadow magazine, and a rampaging Creature from the Black Lagoon,1954. Next to Moses and Aaron is the figure of Wonder woman, inspired by Gal Gadot, but modeled on a toy bank. The large painting is not stretched but hung with grommets, like a banner. The painting renders a complex and discordant scene, complete with disparate patches of old and new, high, and low, spiritual, and earthly, Jewish, and Israeli. The painting displays an eminently modern character. The title implies a sense of existential irony as the Children of Israel accept the Law. “We really appreciate this God, but where have you been?”

8) Golem Maker (The Metaphor of Jewish Modernism), 2017 Acrylic on wood panel, 72” x 96”

This work encompasses both the legend of the Golem and the writings of Walter Benjamin 1892-1940, Gershom Scholem 1897-1982, and R.B. Kitaj ,1932-2007. On the left side of the painting is an Amazing magazine cover from the Golden Age of science fiction rendered as a poster. The artist posed as the model for Rabbi Lowe, the creator of the Golem. Instead of holy garb, he wears a WW I Gas mask as a "safety" precaution from the divine powers. This also refers to the war paintings and prints of the German artist, Otto Dix, and the horrors of the Twentieth Century. A model of the Second Temple is displayed on a table covered with house plants. Like the Temple, the table no longer exists; it was copied from a photo taken at the artists’ deceased parents' home in Brooklyn twenty years ago. There is an Egyptian head, a symbol of pagan resurrection, and an oblique reference to the Exodus story. A small figure (Adam) contemplates the Temple from inside the plants, a prescient view from Paradise? On the right-side Dr. Frankenstein and his Monster are referenced from the 1931 horror movie, (Colin Clive & Boris Karloff respectively) and represents another story about making artificial life. They serve here as participants in the Golem's making. It is said that Mary Shelly, the author of Frankenstein knew about the legend of the Golem and used it as an inspiration. The figure of the Golem is derived from a Mannerist painting by Rosso Fiorentino, Dead Christ with Angels, 1524-7. The powerful torso of Christ as a symbol of Western Christian painting is appropriated for the image of Golem and is purposefully inverted. Strewn with flowers, a model of the Alte Neue Synagogue in Prague rests on his chest. The interior is from the Eldridge Street Synagogue in Manhattan and represents a European- style shul. The allegory is one of artificially making life through religious practice, mysticism, or art. It also charts the new Jewish identity as created and conceived through Twentieth Century Modernism, manifested in such personalities as diverse as Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Franz Kafka, Hanna Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Gershom Scholem, Louis Ginzberg, Sigmund Freud, and Aby Warburg.

Even as we strive to define the art of our time, culture, identity, and history are evolving. The artist seeks to map the territory of his own life and ideas within traditional genres, like portraits, landscapes, and studio interiors, but updated and changed for specific emotional and spiritual purposes. He recalls the epic but in a new way with faults and frailties, as a bold re-vamping of Expressionism conversant with both high and popular cultural ideas. There is an optimism and humor in his work, rammed against the self-confessional and a knowing acumen of later life. As the viewer is encouraged to call upon categories of the self, history, and imagination, art is used as a force for creative transformation. Silverstein reminds us that there is always something more to perception, memory, and imagination than we could ever suppose.